Northern Dental Access Center Expansion through Service to “Competitors”

This is one in a series of six case studies of nonprofits charting their financial strategies through the pandemic. These studies were performed as part of the “discovery” phase of the Nonprofit Financial Commons, and they have helped to collectively inform and inspire our work. We are deeply indebted to NDAC for its staff’s willingness to share this story of daily strategic observation and action.

This case describes Northern Dental Access Center (NDAC), a Minnesota-based, rural-serving nonprofit dental practice with an annual expense budget of around $4 million in earned revenue. Even though its primary revenue is earned, the organization does not set the rate of payment — Medicaid (the payer) does, and that rate is far lower than the real cost of service.

The organization has, within that basic reality, grown significantly over the past decade, but its niche has been carefully negotiated. When the local market, made up primarily of for-profit practices, shut down for all but the most extreme emergencies during the pandemic, the organization renegotiated its niche with a wide range of partners, including contractors and volunteers. Some of the ways it ended up standing in for its neighbors may pay off in the long term.

The growing strength of NDAC lies in the marriage of its commitment to mission to a deep attention to detail. This commitment leads it to maximize of the number of people who can be served—under even the most restrictive of conditions—while not losing the capacity to rebound to scale, whatever that may prove to be in the future.

ENTERPRISE MODEL: Primarily Fee for Service

Nonprofits who use a fee-for-service enterprise model primarily receive those fees directly from individuals, through a third-party payer such as government or private insurance, or a combination of the two. Sometimes the fees may be subsidized by other supporters of the organization. Fees for service is far and away the largest revenue source for the nonprofit sector, accounting for more than $1 trillion in revenue each year, but the lion’s share of that flows to major health and educational institutions many of which have buffers in reserves and endowments.

RISKS

For nonprofit fee-for-service organizations, pricing is always a concern, as are proper capitalization and fitting the size and scope of the organization to its market. Risk often comes from misunderstanding the market, or the timing and scale of costs required to serve that market in ways that build trust and brand loyalty. Product quality and the ability to make good on brand promise are additional internally driven risks. External risks, of course, include being rendered inactive by external circumstances (as in the pandemic closures) and losing momentum, thus eroding the core resources necessary to providing the promised service and losing vibrant relationships with customers.

In this case, the fact that the primary payer is Medicaid brings with it many of the same problems government-funded programs experience, in that Medicaid does not pay full costs and therefore can leave the organization with problems of cash flow and insufficient operating money.

There are many fields in the United States in which nonprofits and for-profits serve the same market — for instance, the performing arts, health care (hospitals, nursing homes, home health care), and the production of news. There is also a history in the United States of prioritizing for-profits over nonprofits in some of these fields by legislating against “restraint of trade” in the open market. Suits have been brought and bills passed to protect for-profits against any undercutting of their interests by nonprofits working with a subsidy of some kind. But the last forty or so years have also seen an explosion of for-profits into traditionally nonprofit spaces, where they exist primarily on money spent by government for the public good. Where there are no or insufficient government subsidies, however, and both nonprofits and for-profits exist primarily on public money, the public good has sometimes suffered dearly. This is arguably true with nursing homes, journalistic news outlets, and for-profit colleges.

Dentistry is one field in which for-profit providers often guard their market share, in part by resisting the emergence of nonprofit providers even if their role encroaches in only a minor way on the for-profit market. This leads to a serious lack of access to affordable dental care for people with lower incomes, and that, in turn, leads to any number of problems related to community health and wellbeing — the public good, in other words. Despite widespread need and, critically, the reluctance of some for-profit providers to take Medicaid, which reimburses only a portion of the costs of delivering care, nonprofit dental clinics remain few and far between, with many of them affiliated with larger medical institutions who have the power and heft to overcome the legal and regulatory barriers placed in their paths.

THE ORGANIZATION: Northern Dental Access Center

Northern Dental Access Center, serving a primarily rural and low-income area, is one of a few independent safety net dental centers across the state of Minnesota. It took the organizers, drawn from concerned groups in the public and private sectors, seven years to build a stakeholder environment among local dentists and others who trusted them enough to allow the effort to take firm root. Still, even then, Northern Dental started small, using a patchwork of different forms of startup capital since grants were thin on the ground. The donation by MeritCare Health (since absorbed by Sanford Health) of a one-year-free lease for space allowed the organization to use the money they had raised for space to buy new equipment. Area dentists donated their services, which prevented a heavy investment in key but temporarily idle personnel even in this highly regulated professional field.

Northern Dental’s enterprise model is primarily fee for service, contracted directly by the party receiving that service. That party has a choice (whether that choice is real or theoretical) in where to “spend their money,” or in this case, their Medicaid dollars. The endeavor therefore requires not only skilled and licensed professionals to provide dental services, but also systems and staff that can optimize the transactions with the third-party payer — in this case, Medicaid, which many other dental providers do not accept but in which Northern Dental specializes. This virtually ensures that Northern Dental will continue to grow if they track their market and keep their highly sensitive enterprise formula balanced—and if Medicaid benefits are not limited. (The last section addresses this in further detail.)

In other words, Northern Dental must be able to contract for the right number of dentists with the right skill sets for the population expected. From there, other questions evolve about geographic span and facilities. It may not be a formula for getting rich, but it does make sure people who need dental care get it, which is by no means a given in dentistry.

PRE-EXISTING CONDITION

As we stated in the introduction, Northern Dental’s great strength lies in its commitment to mission and attention to detail. NDAC always maximizes of the number of people that can be served without losing capacity. Erica Lundberg explains how and why, and in doing so illustrates the complexity of nonprofit financial management and planning:

Each dental procedure has a code and a fee. We submit claims to MCOs that manage Medicaid for the counties we serve, and they reimburse us based on negotiated contract rates. Minnesota has one of the lowest reimbursement rates for dental treatment, so in reality we receive roughly 50% of those fees. The other 50% is revenue that we have to write off our books every year. We call that “contractual allowances,” and it is lost revenue — nothing we can expect to capture — so we budget knowing that. We continue to track the larger production number to be clear to funders and stakeholders about the true value of our services. It is also a consistent reminder that we are a nonprofit organization, taking on work that is genuinely not “profitable.”

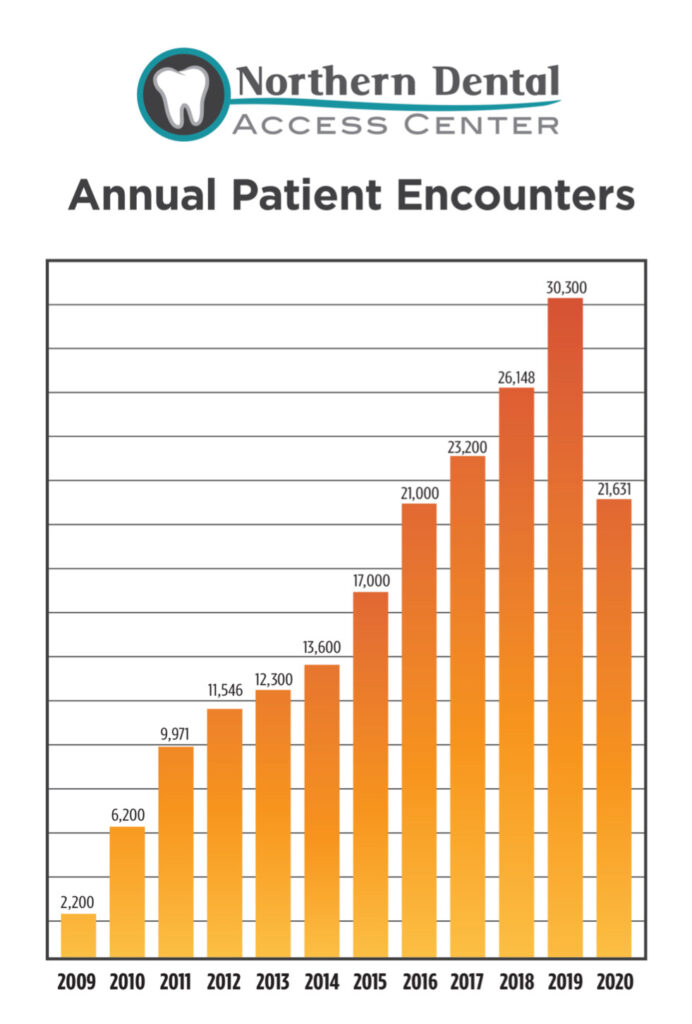

Even with this built-in need for subsidy, the case for Northern Dental’s service is compelling, and the organization was on a steady growth trajectory through 2019 when its expenses hit a high of $4,363,963. By then, it had multiple clinic sites and well-managed systems for patient care and billing. It also had an extensive system of supporters, including a few local philanthropies providing charitable support to bridge the gap between Medicaid and the true costs of service while providing some capital for growth.

Amid Growth, the Pandemic Hits

For Northern Dental, growth requires the establishment of fully fitted out and staffed physical sites, so when the flow of revenue suddenly stops, it presents immediate solvency problems. In a time of growth, and with relatively low margins of available cash, the impact of COVID could have been devastating for Northern Dental, which was not allowed to do any but emergency business under Minnesota’s statewide restrictions for a portion of 2020.

The state first closed all dental clinics, and subsequently amended that order to allow only tightly defined emergency services. Thus, the bulk of Northern Dental’s revenue was immediately compromised for what was to be an indeterminate period. Northern Dental’s patient load declined precipitously. Lundberg reports that four thousand appointments had to be cancelled immediately, and the cancellations caused earned revenue to plummet from $600K monthly to as low as $20K in Northern Dental’s worst months of 2020. Most of the staff of the two clinic locations were furloughed within weeks.

Jeanne Larson, the executive director, drew up a fallback budget that projected up to a $1.3 million loss, understanding full well that the situation could end up closing the organization entirely.

REPLICABLE RESPONSES

Increase Revenue and Decrease Expenses — STAT!

A suspension of the ability to do business could be fatal to an organization primarily dependent on fee for service. But NDAC, having proven its value proposition, amped up its grant writing. Larson, based on Northern Dental’s track record and reputation, took a leap of faith, submitting grant requests to funders that had never heard from the center before — at one point, writing eight applications in eight days. The strategy brought in $156,000 in grant money over the previous fiscal year. The strategy might not have paid off so handsomely, nor been an advisable use of the executives’ time, in another year.

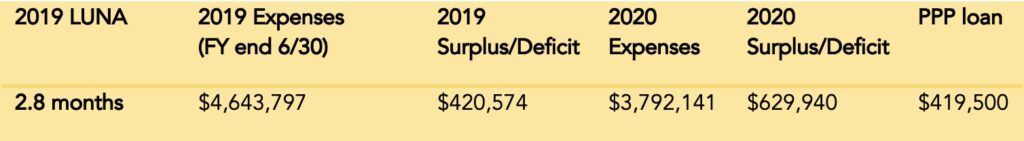

Expenses were reduced by $250,000, largely from not having to pay fees for contracted dentists and other costs related to service delivery. While this was going on, the organization applied for and received a PPP loan worth $409,500, which was later forgiven. That loan allowed the organization to retain the staff that kept the organization on formula, resulting in a surplus of almost $600,000.

Seek Out Information as Early as Possible to Adapt as Quickly as Possible

This small but well-networked organization sensed it might be in for a crisis of unknown proportions and timeline as early as December and began what was to be an extended exercise in educated agility. Meanwhile, in an act of great prescience, they brought up their stores of PPE, buying it wherever it was available.

Board State of Emergency: Good Governance in the Face of Immediate Risk

By mid-March, the state of Minnesota had ordered most of NDAC’s work to cease. Around that time, Northern Dental’s board of directors realized the need to suspend their more rudimentary governance activities so staff leadership would have not just more time but more independent decision-making capacity and administrative “powers.”

Thus, with the degree of strategic immediacy the situation required, the board declared an organizational “state of emergency” to allow for more rapid movement. Larson monitored the external environment while Lundberg monitored their operations. Clear reorganization granted the administrative staff more latitude in a shifting landscape while recognizing and confirming that the board was not simply relinquishing its responsibilities.

Immediate and Constant Communication to Stakeholders

One consequence of the suspension of services was that NDAC’s patients, contracted care providers, and “non-essential staff” were cut off from day-to-day, in-person contact with the organization. This left a vital set of hard-won critical relationships in danger of atrophy, so Northern Dental centered a communications strategy that was meant both to inform and nurture.

Subject: COVID-19 status — Northern Dental Access Center closing

Date: Wednesday, March 18, 2020, 2:49:00 PM

Importance: High

I’m sad to report this decision that we made at noon today: Due to circumstances beyond our control, Northern Dental Access Center—Bemidji will be closed on Friday, March 20, until further notice.

Patients with scheduled appointments will be contacted by our office for rescheduling. We will make every effort to respond to patient phone calls on a regular basis.

Northern Dental Access Center—Halstad will be open on a limited schedule through this week, and closed starting March 23, until further notice. Patients are asked to call ahead for further information.

Urgent dental triage will be available on a limited schedule, by telephone, and when necessary, we may bring a dentist in to complete an emergency procedure, to CURRENT PATIENTS only. With all the dental offices in the region closing, we are not able to accept patients who have a dental home elsewhere.

Updates can be found on our website at www.northerndentalaccess.org

Tailored communication with all stakeholders became a daily concern, but it was already at the heart of the organization and its the organizing tradition. Here’s how Larson describes the history, culture, and return on investment of Northern Dental’s approach to communication:

Northern Dental Access Center was created through a remarkable community collaboration, and we serve a large number of people all over the region. We have always had a commitment to transparency and accountability, and we took cues from other public officials who — even when information was constantly changing —understood the value in keeping people informed. To be such a critical community asset and then just shut down added to the strain faced by patients, dentists, emergency rooms, and others. Our best remedy was as much communication as possible, assuring stakeholders that we were doing the very best we could to overcome this time and emerge intact. That communication helped build trust so they could be patient and empathetic with our efforts. And being open and honest with funders brought them into our problem-solving work — they responded with generosity, flexibility, and gratitude. Had we kept our worries and strategies to ourselves, we would have been trying to do it all ourselves—which was simply not going to be enough to survive the challenges we faced.

On-Site Staff Reduced to Fit Allowable Caseload

A seven-member direct care staff was kept on for those few patients who fit the emergency guidelines. It was here that the organization’s core commitments, values, and principles became evident in a series of decisions that would eventually put the organization back on its feet and in what Larson calls “the sweet spot” of their practice, serving the greatest number of patients possible in a way that sustains the organization over the long term.

Strategic “Extravagance” for Human Resources

A good portion of Northern Dental’s strength lies in its staff, and it tries to recognize and reflect that understanding in policies that some might see as “extravagant,” especially in tough times, but which they see as serving everyone’s best interests. For instance, the organization pays the full cost of family medical benefits to all full-time staff, and it defines “full time” in the broadest way allowed.

DT: July 30, 2020

TO: All staff

FR: Jeanne

RE: “Full-time” hour threshold

Thank you all for your continued commitment during these difficult times as we transition to increasing our services to patients.

You’re probably aware that we are monitoring our capacity, production, and efficiency on a daily basis to be sure we can sustain a revenue stream that preserves our ability to survive the disruptions we are seeing due to the COVID pandemic.

Because I recognize that the staff scheduling changes week to week, I would like to ease your worry about the minimum weekly hours that we typically require to be considered “full time” and maintain health insurance benefits.

Through December of 2020, we will continue to cover your health premiums, even if you work fewer than 32 hours in a week. While this blurs the lines between full time and part time for the coming months, this change applies to employees who are currently enrolled in our Blue Cross/Blue Shield plan.

Later this fall, we will better understand our employee health plan options for 2021 and the associated costs. I wish we knew more now, but this interim solution is our best attempt to demonstrate our commitment to you, and our gratitude for your work. Please communicate with your supervisor about your weekly schedule, and feel free to reach out to Jenn, Erica L., or me if you have any concerns.

The same sensibility carried through for the line staff that remained on duty during the height of COVID, who were afforded a generous $600/week bonus for the risk they undertook. Lundberg said provisions like these put them in good stead when other organizations tried unsuccessfully to recruit their staff, even during the pandemic.

Working Every Detail in a Tight Margin Environment

Once restrictions began to lift, Northern Dental’s recovery process started almost immediately. Lundberg was tasked with working through the details of gradually reinstituting services. It was a painstaking job that required matching patient needs to the regulations and requirements as they evolved day by day and to the staff and the professional dentists who contract with Northern Dental.

THE DAILY TRACKER

When we were ready to start calling back employees from furlough in the summer of 2020, our guiding principle was that we couldn’t afford to lose money. Erica [Lundberg] created a daily tracker on an Excel spreadsheet that included the wages expense for each employee and dentists, an average infrastructure cost (mortgages, supplies, lab fees, etc.), and the patient production for each day. Because we know what our Medicaid reimbursements are (as a percentage of production), she could track each day and whether we made or lost money. In real time, she could see what employee, patient, and provider mix was most effective. She used that tracker as a planning tool by inserting future scenarios to determine the financial and patient impact of each employee return….

With daily incremental growth in coming back from COVID, she could identify the tipping point when it was financially feasible to bring the next person back. One by one, we were able to get everyone back before the federal added employment benefits expired and maintained a steady increase in patient encounters. Part of our calculations included the monthly costs to maintain every employee’s family health insurance coverage throughout their entire furlough; we wanted to ease the minds of our employees during that uncertain time and demonstrate our long-term commitment to them so they would trust our intent and be able to stay home and stay safe without worry. Even now, long past the most tenuous times, Erica uses that tracker to guide our decisions. It’s become a highly effective management tool. — Jeanne Larson

Since this was a core management orientation of the whole operation, this process wasn’t brand new, but this deep dive into the details left them with a much better understanding of where they might achieve more efficiencies in their day-to-day practice. Those efficiencies, both Erica and Jeanne assert, will leave more room for meeting other needs.

On another front, Northern Dental left no resource stone unturned when it came to government funded loans and grants (see approach to private grants above).

Federal Provider Relief Round #2 (they were not eligible for Round 1) = $60,000

Federal Provider Relief Round #3 = $346,000

Federal Rural Provider Relief = $18,200

Federal Provider Relief Round #4 = $157,000

PPP – Draw #1 = $419,000 (forgiven)

PPP – Draw #2 = $479,000 (forgivable)

EIDL = $10,000 (forgiven)

Additionally, Northern Dental was awarded $10,000 through the state nonprofit relief fund (administered through the county), and it plans to pull down federal employee retention credits to cover the costs of their payroll taxes. They hope that might add another $50,000–$60,000 from that program.

Larson says that the money did not come to find them but was the result of vigilance and working every network. “I will say that the vigilance necessary to capture these programs shouldn’t be underestimated. I know of many of my peers who didn’t apply because they thought it would be too cumbersome. or thought they wouldn’t be eligible, or they didn’t want the federal oversight. As an aggressive fundraiser, I’m not shy about applying for everything I can find, and I’m always scouring the landscape for opportunities.”

Nimble Refitting Rather than Downsizing

Several organizations in these case studies reduced or redesigned some services while expanding and initiating others, and Northern Dental was no different. The organization continued to be patient- and community-focused, and instead of using their now well-organized system merely to address the portion of their own patients they were allowed to see under COVID emergency guidelines, they opened capacity to meet the larger community need unaddressed and unmet by more mainstream practices.

Larson recalls, “In the midst of the harshest restrictions, many private practice offices closed completely — some because the dentists themselves were in a high-risk category due to their age, or because their staff did not want to risk their own safety. At the request of private dentists, we opened our few appointment spaces to address their patient emergencies.… In addition, another regional safety net dental practice was not able to reopen, and we agreed to take their emergency patients as well. This further cemented our role as a community partner and asset, but did place even greater burdens on our limited capacity at the time.”

This last point about reinforcing Northern Dental’s role as a necessary partner in the area’s dentistry community speaks to the importance of creating social capital — even, and maybe especially, in the direst of circumstances. For Northern Dental, which carefully eschews any hint of competition with its neighbors, this opportunity was momentous.

ONE YEAR LATER

Larson reports that even as the organization has managed to adjust in response to extreme disruptors, it continues to face significant ongoing environmental tumult in its “market”:

The expanded eligibility for Medicaid enrollment that was implemented during the height of COVID has only expanded our target population, yet our facility and workforce capacity remains stagnant. Simultaneously, the strain on the private sector has forced many to reduce capacity or close altogether, further reducing dental access for the general population in the region. Demand for care is crippling and creating another set of challenges.

On top of these issues, she adds, “The state has also suspended annual renewals of Medicaid coverage for almost two years now, and soon that will end, and all enrollees will be required to recertify their eligibility. People in the know on this are expecting that 30–50% of current enrollees will be cut off sometime this spring.… That will create a nightmare for us and for patients.”

So, in other words, nothing has “calmed down” for the organization or its vulnerable patients, but the organization has brought some of their pandemic-inspired practices forward:

The Daily Tracker that informed how far we could stretch a team’s capacity taught us that we could increase the amount of dental care provided in each patient appointment. And we have decided to keep the idea that employee health insurance isn’t tied to a minimum number of hours in a week. We have learned that this is a wonderful way to support the younger generation of workers who desire a different approach to work/life balance.

In these times of the “Great Resignation,” we have seen long-term loyalty and retention because we provide the flexibility of time without sacrificing employee and family health. Many still face unpredictable childcare situations, erratic school closures, and periodic exposures and COVID cases.… It has eased so much strain on them — and on our supervisors, who simply don’t have to monitor this aspect of the work.

At the same time, the organization is attempting to move ahead with further geographical expansion. Larson discussed the organization’s current ambitions, which are based on a business model that is operationally sustainable but requires around $4 million in capital for facilities and equipment:

Regarding our expansion project, we are working in concert with Apple Tree Dental, another successful nonprofit safety net dental provider in the state, to improve access to dental care among the Medicaid population in the Detroit Lakes and Becker County (and adjacent counties), where more than 75,000 Medicaid enrollees live. Area private practice dentists have reached out because of their continued frustration with being unable to serve the growing demand for care among people they are ill-equipped to serve.

We hope to build a new clinic in Detroit Lakes, and Apple Tree hopes to expand its current facility 25 miles away in Hawley, so that together, we can provide a continuum of care that leverages our unique strengths. Our model sets a new standard for efficiency and effectiveness for in-clinic preventive and restorative dental care; Apple Tree is highly successful in its outreach to community settings like Head Starts, nursing homes, and more. It’s an exciting partnership that can demonstrate even more success in bringing dental access to underserved, rural communities.

Northern Dental Access Center has just been awarded the 2022 Outstanding Rural Health Organization Award by the National Rural Health Association.

APPLICABLE RESEARCH: SURVIVAL OF THE FITTING

The largest source of revenue for US nonprofits by far (at $1 trillion in 2015) is private fees for service. Much of these fees flow to health organizations, which are often megaliths in comparison to nonprofits in general. Following that revenue pool as a slow second is the federal government, which is around half of that at $491 billion.

Fees for service that require not just billing but third-party billing by code are labor intensive in terms of transactions and require sufficient reserves to allow time to collect what is owed after the services are rendered. This requires administrative systems that are well coordinated with service delivery and well monitored.

But even if a modestly sized nonprofit can organize itself to establish and manage these kinds of intensive transactional systems, it is often left with problems of undercapitalization and, in contested fields, market jealousy. Here is where a rule of “survival of the fitting” can be brought to bear. In Images of Organizations, Gareth Morgan proposes a number of basic metaphors we can use to shape our approaches to establishment, management, and growth of organizations serving those with constrained incomes in turbulent or potentially turbulent environments. One of these is the organization organized around flux and transformation, a metaphor that well suits civil society. From the NOBL Academy’s “How 8 Organizational Metaphors Impact Leadership”:

People who see organizations in terms of flux and transformation have embraced uncertainty, complexity, and even chaos in terms of the changes their organization is experiencing. You can think of this metaphor as an evolution of Organism — rather than thinking that simply the environment changes and then the organization must respond in kind, this metaphor says that both the environment and organization influence one another, and both must respond to change.

This way of working seeks to make itself effective and trusted through partner-informed and partner-fueled adaptation.

[U]nder this paradigm, leaders are called to experiment with small, safe-to-fail changes and then marshal resources to further successful experiments while shutting down failures; in contrast to the organism view, changes within an organization also spur changes in the environment

In the case of Northern Dental Access Center, the organization has social capital built into its DNA as a result of a lengthy period of cooperation (even with potential “competitors”) during its founding phase. These relationships have since been reinforced through constant active communication with stakeholders, use of local dentists as non-full-time contractors, and willingness to serve emergency patients of for-profit practices during the worst of the pandemic. Thus, it has used cooperation to establish credibility and networks of support, a strategy that has replaced competition as an effective route to market capture and expansion.

Its recent award from the National Rural Health Association is a conversion of this social and local cultural capital it has accumulated into symbolic or reputational capital. But to complete the virtuous cycle, financial capital has to complete the launch pad for its next phase — $12 million in capital, to be exact.