Resources

Courses NFC Presents Tools

Nonprofits and QuickBooks Online 2025: Optimizing, Enhancing, and Weighing Alternatives

If your nonprofit relies on QuickBooks Online, this course is essential. Access all three sessions on demand — anytime!

NFC Presents Webinar

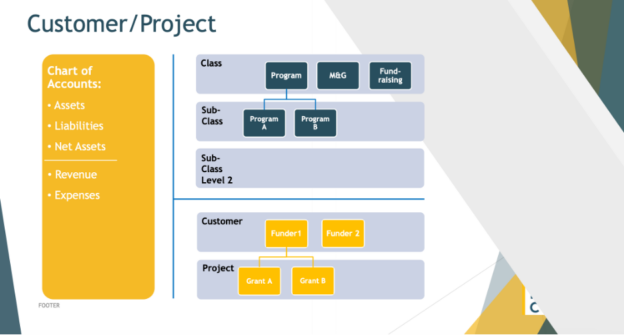

Chart of Accounts –Webinar Recording and Resources List

Your chart of accounts should be built with an eye toward accurate financial storytelling, strategic impact, organic logic, and ease of use.

NFC Presents Webinar

Fiscal Sponsorship – Webinar Recording and Resources List

Fiscal sponsorship is an alternative to incorporation and its attendant bureaucracies, an option for even well-established organizations.

NFC Presents Webinar

Cash Flow – Webinar Recording and Resources List

Good planning and management of cash flow lets leaders make decisions in advance of problems so commitments can be met.

NFC Presents Webinar

Membership Organization Model – Webinar Recording and Resources List

Nonprofits that master the membership organization model can unearth riches and momentum heretofore unrecognized.

Article NFC Presents Webinar

Nonprofit Boards – Webinar Recording and Resources List

What exactly is the board’s role in helping to steer a sound financial course for your nonprofit?